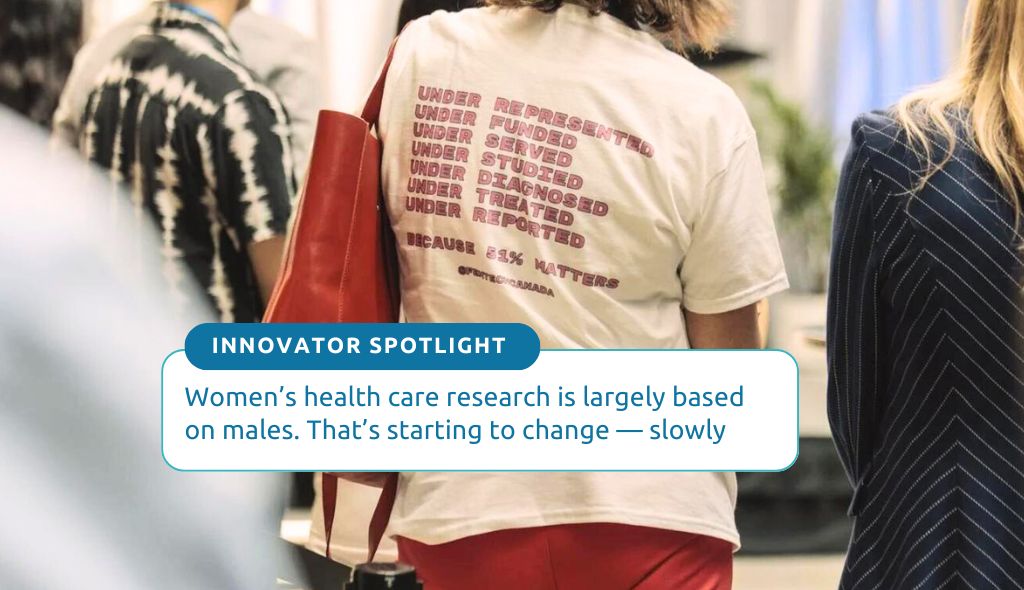

Given that women’s health issues directly affect at least 50 per cent of Canadians, it’s shocking how much we don’t know about this subject. Discoveries that might expand our understanding of women’s bodies and sex-specific characteristics of disease have been consistently underresearched and underfunded — not just in this country, but around the world. It wasn’t until 1997, for instance, that Canada introduced formal recommendations to include women in clinical trials. Nearly two decades later, in 2016, the American NIH finally adopted a policy requiring researchers to separate data based on male and female subjects.

The lag in recognizing that chromosomal makeup can affect everything from overall health to the ways in which people respond to medications has had significant repercussions. The pipeline for innovation has been based on a male paradigm — even today, there’s a marked skew when it comes to the originating cell lines used in research, with evidence of scientists using exclusively male cells in more than half of the studies in which the sex of cell lines was documented. In experiments where cells are being tested to see how they respond to certain drugs, any data may only reflect how that medication affects cells with an X and a Y chromosome — which means the process may fail to highlight effective treatments or worrisome side effects for people who have two X chromosomes.

Today, there’s still murkiness when it comes to the efficacy of many drugs and devices for women. For instance, while estrogen receptors are located in cells throughout the body, clinical trials require female subjects to use contraceptives such as birth-control pills to ensure there are no inadvertent pregnancies (to protect both potential fetuses and the sanctity of the data). As a result, we don’t have a clear picture of how regular hormonal fluctuations affect the way medications are absorbed and metabolized. To many of us, this black-box approach to women’s health may spark anxiety; for Brittany Barreto, it represents the seeds of possibility.

An entrepreneur, venture capitalist, podcaster and consultant with a PhD in genetics, Barreto believes we’re on the cusp of a revolution in this sector. According to data from her FemHealth Insights, more than 60 per cent of femtech startups were founded in the five years leading up to 2022, and 85 per cent of femtech companies are female-founded — the highest percentage of female founders in any industry. Much of the change in this realm, she says, is being driven by patient advocates themselves: “Think of a woman in STEM who says, ‘It’s unacceptable that it took me this long to be diagnosed with X — and by the way, I’m an engineer, and I’m going to find a solution.’” Personal understanding drives momentum for both entrepreneurs and investors, she adds; if a founder is pitching innovative tech to tackle hot flashes, or urinary incontinence, or menstruation, and nobody on the other side of the table has experience with those issues, they may not be inspired to invest.

Health care is one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing industries, accounting for 10 per cent of the GDP of most developed countries, and women are a vital force in this market, responsible for a staggering 93 per cent of over-the-counter pharmacy purchases worldwide, according to one survey. Some projections suggest femtech alone could be worth at least $4.8 trillion globally within the next two years. “I’m an optimist, and to me, this reeks of opportunity,” says Barreto. “It reeks of money and impact and ROI and GDPs and happier, healthier communities and people. We’re more than our period and our fertility — we are bones, we are brains, we are guts, we are autoimmune diseases, we are hearts. There’s a lot more that goes into women’s health. And it hinges on understanding that sex and gender needs to be incorporated into science and health-care innovation.”

At MaRS Impact Health, a recent conference on medical innovation, leaders in femtech shared their experiences — as scientists, entrepreneurs, researchers, investors and end users — and reflected on the evolution of the sector. One of those leaders was Barreto, who moderated a discussion with Jocelyn Wessels, co-founder and CSO at Afynia Labs, a Hamilton startup that has developed a blood test for endometriosis; Sabriya Stukes, partner at SOSV, a venture capital firm that focuses on planetary and human health, and Danielle Graham, co-founder of women-in-tech network The Firehood and partner in Phoenix Fire, an angel fund for early-stage female-founded ventures. Here’s what they had to say.

Brittany Barreto: Historically, femtech has been relegated to, as I describe it, boobs and tubes. But women are more than just our periods or our fertility — we’re now seeing femtech diversifying to cover the whole female body. What innovations and technologies coming out of Canada and your network are you excited about?

Danielle Graham: It’s not just digital health, which a lot of venture capital investors focus on, but deeper technologies and hard tech. So, VoxCell and their 3D printing or FemTherapeutics and their customizable pessary for pelvic health or Hyivy and the extraordinary story of Rachel Bartholomew — we’ve seen these solutions come to the forefront in the past five years. Our first pitch competition at StartupFest, I remember how many founders had new reusable pads and tampons — the entire table was covered in them, and then someone spilled a drink, so we had something to soak it up. It was wonderful to see the openness and sharing and comfort level.

Brittany Barreto: Sabriya, do you have any advice for femtech startups looking to acquire funding?

Sabriya Stukes: When Afynia Laboratories came across our radar, Jocelyn and her co-founder Lauren Foster had this crystal clear vision of how their test could meaningfully impact people’s lives — right when they’re speaking with their doctors and saying, “I don’t know what I have — it could be endometriosis, it could be something else.” They had a clear vision, they had the data, they had a sense of who their customers were going to be, they had a business model that made sense. For anyone thinking about starting a venture, saying, “I might have a technology that can address a big problem,” is important, but that does not make a company. Really think about all the other things you’d need, even if they’re hypothetical — like, “I think X would be my biggest client.” You need to be able to have that conversation even at the earliest stages.

Brittany Barreto: Jocelyn, you’re a scientist by training; where did you learn to build your business plan?

Jocelyn Wessels: I’m kind of an accidental entrepreneur. When you see something and it doesn’t make sense — like, it takes five to 12 years to diagnose endometriosis, so people are suffering for years with chronic pain … that hurts my heart. After talking to patients, I was like, “I have to do something about this.” My co-founder and I decided to leave our academic positions and start a company. Our vision and mission changed immensely. I had to acknowledge that even as a well-educated woman in science, I wasn’t a well-educated person in business. I needed to learn how to surround the science with business. And a lot of that came from mentors, including people on the team with MBAs.

Sabrina Stokes: When we’re thinking about closing the gap in health care for women, it shouldn’t just be up to women to figure out the solutions and the funding, although we do need to be in the room. I encourage all the men — if you have funds, or if you’re founders, ask yourselves, “How can I help close that gap?”

Brittany Barreto: I’ll go one step further: If you’re a male with finances wanting to support women’s health, please also ask a femtech VC to support you in your investment decisions. Either be a limited partner in a femtech fund — of which there are now about 13 in the world, compared to just one in 2019 — or ask if they have early-stage companies that they’re excited about that need angel investing.

Brittany Barreto: One of the barriers in femtech is that there’s nobody reimbursing patients when they’re accessing new services. What does that landscape look like? How is the business of women’s health care changing?

Jocelyn Wessels: Right now patients are paying out of pocket for (Afynia’s) test, and a lot of them are happy to do so: Spending 12 years suffering in pain versus paying a couple of hundred to maybe get some answers sooner, or at least get to the right care provider? For a lot of women, that’s a no-brainer. I’m not trying to make light of spending money, but we do get asked about our reimbursement strategy, and that’s been hard for us to understand (compared to) juggling all the other balls of running a full-scale lab in Hamilton and applying for funding from the government or pitching to VCs. As soon as we can unlock reimbursement, we’ll have a much wider market. But reimbursement is not the same in Canada and the U.S., not the same in every state, not the same in every province. If there’s such a thing as an expert in reimbursement, come talk to me.

Brittany Barreto: If there was someone from the Canadian government listening, how would you suggest that they accelerate the development of femtech as a whole?

Jocelyn Wessel: I’m a researcher at heart — you have to start with the research dollars, though I’ve actually seen that coming in Canada. There’s momentum building here. But as a two-and-a-half year-old company, we’re looking at the valley of death (the gap before a startup brings in revenue), like: “We have the patents, we have the science, we have the lab, but can we make it?”

Brittany Barreto: What does the future of health and wellness look like based on what’s happening in the femtech movement today?

Sabriya Stukes: I think it looks very bright. But it’s kind of an all-hands-on-deck movement. The more funding we put into research, the more tools and technologies we’ll see because we’ll understand the biological symptoms or the reasons things are happening. This discussion reminds me of a quote from Maya Angelou that goes something like: You do your best until you know better, and then you do better. I hope that this information, these statistics, these stories encourage us all to do better.